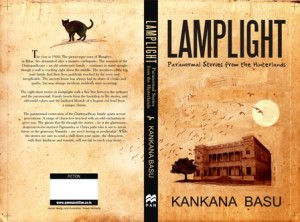

About the author: Kankana Basu is an author, illustrator, columnist and a travel writer. Her first novel Cappucino Dusk was long-listed for the Man Asian Literary Prize. Read her interview here. Below you can read a sample story from her book, Lamplight. Courtesy: Kankana Basu.

The Wedding of Tigmanshu Pramanik

If only I had died with a slightly more dignified expression on my face. The pretty village belles then would have remembered and grieved over me in their dreams. But alas and alack……

Death came swooping down on me just as I had my face turned to the grey stormy skies with my mouth wide open. I must have looked really silly. A storm warning had been issued to the seaside town of Digha and people were running helter-skelter, tying their fishing boats and folding up their beach stalls. I should also have been heading homewards had it not been for a palm tree loaded with palms, one of which was secreting a delicious juice that fell drop by drop to the ground from a great height. I had my mouth open and was prancing from one position to another and succeeding in catching each falling drop into my open mouth pretty successfully. It was exhilarating!

‘Kolshi, palaa re palaa, jhod aasche- Run Kolshi run! There’s a storm coming!’

I ignored the cries of warning from the men of my locality for the simple reason that I abhorred the nickname they had forced on me. Kolshi! Ugh!

Agreed that at seventeen I weighed a hundred and twelve kilos and was shaped like a barrel but to call a sensitive teenager Kolshi, an urn, was the height of irreverence, don’t you agree?

My official name is Tigmanshu Pramanik, a name that, according to me, carries with it an unmistakable stamp of aristocracy besides packing a lofty auditory punch! I had been named Tigmanshu by the youngest scion of Kumkum mashi’s employers, the Chattopadhyays of Monghyr. Balai Chattopadhyay or Lekhak Kaku (my novelist uncle), who was the father of my summer friend Master Montu, had chosen the name for me in my infancy.

My mother had been visiting Kumkum mashi the summer after I was born. Mashi, to show me off to the Chattopadhyays, had carried me to their house as a cute little baby weighing nearly three kilograms. Hugely impressed by my birth weight and chubby cheeks, Lekhak Kaku had chucked me under the chin and said that a robust baby deserved a robust name. ‘Tigmanshu- I will call him Tigmanshu,’ he had chuckled delightedly, leaning at his desk that had spawned so many famous novels….and so, Tigmanshu it was, since that day. A fine regal name for a fine regal boy.

But these heathens, I tell you…these heathens living in my home town do not know how to roll a dignified name around their tongues, savour the taste of aristocracy and allow it to enter their veins…it seems their veins are filled with cow dung instead of blood! They changed my name to that disgusting plebian abbreviation- Kolshi! Morons, the entire lot! Morons! Ahhh, if only I had been born into an educated family instead of a fisherman’s hovel, I, with my fine thoughts, upright morals and delicately balanced emotions…

Well, to get back to the matter of my sudden demise, one minute I had my face upturned towards the heavens and was blissfully savouring the palm juice falling from the tree and the next minute, a fully loaded palm came loose from the parent tree and hit me hard on the head. I went down, knocked clean to my skull. I fell on a plank of wood, a discarded part of a boat, most probably.

I heard cries of horror from the women. Kolshi’r mathar opor taal podeche re! A palm has fallen on Kolshi’s head! I heard the roar of water. A mammoth wave was bearing down and the women, who were fussing over my supine body, turned and ran in terror. The wave hit the sands, went roaring all the way to the line of palms and while receding, took the plank of wood with my inert body wrapped around it.

And so, I was swept away to the sea and denied the last rites afforded to a dead Hindu male that ensured him his official place in heaven. I watched my mortal remains float aimlessly on the high seas, providing a feast for the fishes and ultimately there was nothing left, only my batik-print dhoti floating lazily in the waters. I hung around in limbo for a long while, it seemed an eternity to me, feeling neither pain nor pleasure at my plight.

Where was I? This was neither purgatory nor paradise, an isolated geography with no signs of man or beast, a no man’s land that should be terrifying. Only it was not! My capacity for experiencing any kind of sensation had vanished with my mortal remains. The realization hit me when I discovered that for days I was feeling neither hunger nor thirst and that sparrows were flying right through me.

I was a ghost!

Reality hit me like a sledgehammer. I was neither boy nor corpse, neither a dweller of this earth nor of the realms beyond it, I was neither truly alive nor fully dead! At this terrifying realization, I’m ashamed to say that I put my head on my knees and wept copiously. I was only seventeen, I had not seen the world, had never fallen in love, never held a luscious female form in my plump arms. I had not even eaten all the food that I wanted to taste before I died- shorshe ilish, lobongo lotika, chingri malaikari and other such delicacies that my aunt Kumkum was always talking about. She worked in the house of the wealthy Chattopadhyays in Bihar, and she would know! The glutton in me was not satiated. Before I could live life to the hilt, the country of eternal twilight had claimed me. What utter cruelty, what supreme injustice dealt by fate to a boy only in his tender teens!

I drifted along miserably for months, years, centuries or was it aeons?

I took to hovering around sweetshops. I drifted over rows of neatly stacked pink-brown squares of sandesh and twirled over the pans of bubbling saffron-scented rosomalai. I waltzed around the lines of small crisp samosas with their potato-pea filling and swooned over khasta kachori. I inhaled the intoxicating vapours of a sweetshop but when I bent to lick or bite the stuff, alas, I just passed through the vats like thin air!

I could have wept in frustration!

After aeons of trying, I finally perfected the art of lifting diaphanous materials by an inch or two. It was a hugely commendable achievement even though I say so myself, and it knocked me out for a while, the effort of mastering that art of lifting lightweight stuff. Don’t ever believe what they tell you about ghosts setting houses on fire and sending furniture crashing and all that ‘poltergeist’ stuff…unadulterated rubbish, all of it! Utter exaggeration! Part of the usual Western propaganda, just trying to prove that their ghosts are superior to our desi ones. I’ve tried telekinesis for centuries and couldn’t even lift a rosogolla off a tray! It is another matter that even if I did lift it, I wouldn’t know what to do with it, not being in a position to eat it.

The good thing, probably the only good thing, in this supremely tragic tale of mine was that I could switch time zones and cross the entire length of the country as effortlessly as taking a walk in a garden. Today, I could hover in Akbar’s court, teasing the pleats of the Begum’s gharara, tomorrow I could blow into Rabindranath Tagore’s lush beard and tickle that great persona and make him laugh. I have to confess that I thought he had a rather weak laugh…

No matter.

What I liked best was to haunt the riverside late in the morning. When the village women, half-dressed and achingly desirable, bathed, washed clothes and splashed each other playfully. I went swishing down in their midst, trying to blow the pallu off one heaving bosom or fan the wet tendrils of hair hanging on another’s face. My ghostly hormones raged within me at such times and I swear I thought I’d ignite with passion or do something quite alarming.

I was also in the habit of going back to the early 1950s and flitting around the Chattopadhyay mansion. Spying on the huge household and the antics of various family members was a favourite hobby of mine. I could see Kumkum mashi stomping around the sprawling house, busy at her chores. There was a streak of grey in her previously jet-black hair. When Ronnyda set off to play a game of football, I followed him to the grounds, cheered along with the rest of the spectators all through the game, though my cries must have been inaudible to all. I even tried to deflect the ball in Ronnyda’s favour with the skills I had attained over the centuries. I liked to think…ahem…that I deserved a share of the credit for the famous goals that led Ronnyda’s team to victory, repeatedly.

Though I was not too taken up by the tomboyish older sister, I freely confess that I was completely smitten by the younger one. I followed Miss Mini everywhere- Mashi had commanded me never to address them without the prefix ‘Miss’- quite like that Mary-character’s lamb in the firangi poem that children from the English medium schools can always be heard chanting.

Too bad for me that a rival ghost from the Monghyr Fort nabbed Miss Mini in the end! An effeminate, long-haired singing ghost with a hairless chest and emerald drops hanging from his earlobes… Eeeeww! Now if it had been me, with my robust physique and Miss Mini, with her charming persona, we would have made for such a winsome couple. But alas, that was never meant to happen…

The only person I was terrified of- imagine a ghost being terrified- was the gardener, Raghu kaka. He had the uncanny habit of halting in his work and staring directly in my direction as I hovered over the gardens. His strange gold-flecked eyes seemed to bore through me and I hastily flitted away whenever he was around.

After a few years of going back and forth, I decided that enough was enough. I had had enough of this phoney grief-stricken existence. I badly needed a memorable milestone before I made my passage into eternity. I needed a real experience.

A good meal…

And a torrid romance…

One of those wonderful traditional Bengali weddings with the bride being carried round the fire seated on a wooden peedi and the groom holding on to his conical headgear, the topod, and trying not to look like he was balancing the leaning tower of Pisa on his noble head, on a particularly windy day. Just thinking of all his brought tears to my eyes.

The more I thought about it the more determined I became. I was hell-bent on going all out and being a part of a real human experience just once in my ghostly existence. But how was I supposed to go about it? I had no idea how to proceed. I knew no shamans, tantriks or other supernatural pimps, who could communicate with spirits and maybe for a small fee, get them to assist me in my ghostly aspirations.

I wafted around in despair wondering whether I would have to shelve my dreams at the very onset, almost before conceiving them, when all at once a swarthy face swam into my memory. Raghu kaka! There was something odd about the man, a gaze that seemed to go beyond the mundane. He could always sense my presence. I distinctly remember that once, when I was teasing his prize-winning roses, trying to dislodge them from their stalks by blowing on them, harmless fun really, and he had thrown a garden hoe at me with deadly aim! It had sailed right through me, of course, but his aim had been bang on target, confirming my belief that unlike other mortals, he could see me very clearly.

Yes, I’d try and hunt down Raghu kaka.

I wafted down to the 1950s again and started searching. Things looked very different. The trees around Chattopadhyay mansion had grown high dwarfing the stately building and the adjoining Nandi house had burnt down. All that remained were blackened stumps of the bungalow’s foundation. I could see a thin crooked woman, most probably of my tribe, flitting around the ruins but I sped away hastily, not liking the look of her. Raghu kaka appeared to have disappeared and I hastened towards the 1960s.

I finally found him walking on a lonely rocky road that led to Badrinath. He looked gaunt and old, much older than when he had flung his hoe at me. I descended respectfully before him but glancing at me fleetingly, he continued to walk at a brisk pace. I flitted around him a bit and finding myself royally ignored, swooped down and fell groveling at his feet. He clicked his tongue in irritation.

‘Tu mera peecha kyun kar raha hai, re mote? Why are you following me, fatso?’

I rushed into speech and told him of my predicament and my burning desire to live a real life, even if for a short time. He gave me a cold look and informed me that he was on his way to do penance in the mountains and beseech the powers that be, to take away the gift of ‘sight’ that was beginning to turn into a curse for him rather than a blessing. Bent on achieving liberation from the accursed ‘sight’, he had no time for fripperies such as my ludicrous request. I wept harder and informed him that he had no idea how tough it was to be a ghost.

‘We are a godless, government-less fraternity’, I wept. ‘Not even a fraternity because such a word implies brotherhood and we are creatures of isolation, perennially operating on the ‘each for himself’ policy. Unlike heaven or hell, there are no kindly custodians to look after us. We are an isolated bunch. There are no social workers, no Good Samaritans assigned to look after ghosts, we are the most marginalized, neglected creatures; the eternal inhabitants of a no man’s land. And since you’re the only person I know who has a certain degree of celestial influence and because you are something of an expert in matters of the metaphysical kind….’

‘Cut out the rubbish and let me walk in peace, launde. Stop harassing me like this. If any pilgrim comes along and sees me talking to thin air, I’ll be mistaken for a lunatic and locked up!’

I only wept louder and clutched at his feet. He turned and uttered an oath.

‘Leave me alone. Why don’t you go to hell, fatso!’

‘I can’t,’ I wailed, ‘there is no place for those like me. Neither in heaven nor in hell!’ But he continued to charge ahead with an air of finality. I’m ashamed to say that I set up a deafening howling at this. I threw myself with force at his feet and created such a flutter that his loosely tied lungi rose billowing over his head and I was left staring at Raghu kaka’s underwear. When the right things fell into the right places, Raghu kaka after a long thoughtful scratching of chin, finally relented.

‘What is it you want from me?’ he asked with a sigh.

My words tumbled out with the force of a monsoon downpour.

Lamplight can be purchased here.