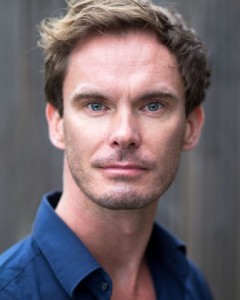

Jason Hewitt is a playwright, actor and author. He was born in Oxford and lives in London. He has a Bachelor of Arts degree in History and English from the University of Winchester and an MA with distinction in Creative Writing from Bath Spa University.

The Dynamite Room is his first published novel and has been longlisted for the Desmond Elliott Prize 2014 for new fiction. Read his interview here.

Below, you can read an excerpt from his book, The Dynamite Room. Courtesy: Jason Hewitt.

The Dynamite Room (Book Excerpt)

She was the only person to get off the train and as it pulled out again, leaving her on the empty platform, she watched the receding line of carriages tail into the distance; the dried leaves, caught in a flurry of air, chased after them down the track. She walked out through the gates into the sunshine and onto the road, but there didn’t seem to be anyone about. The station shop was shut and she wandered back onto the platform and prised her last two pennies out of her secret pocket so that she could buy a bar of Fry’s Chocolate from the vending machine, but that was empty as well. She wondered where everyone was. The station name that swung from the awning was gone; there were just hooks where it had once been. She’d heard about this on Mrs Duggan’s wireless: all across the country, towns and villages were losing their identities and road signs were being taken down. Her mother had written about it too in one of her letters. Six letters, one for every week she’d been away, and all of them folded and folded again until they were small enough to keep safe and secret.

It was a short walk into the village across the Suffolk flatlands, and she struggled along the lane, her heavy suitcase bumping against her leg and the box for her gas mask hanging around her shoulders.The sun blazed over the top of the hedgerow. The first sight or sound of an aeroplane and she’d have to scramble into the ditch; she’d be an easy target for them on such an open road. It surprised her that there was nothing there to stop them from trying to land on it – railway sleepers, rotten tree trunks, old bedsteads or mangled bicycles. All over Sutton Heath anti-glider ditches had been hand-dug to stop the Jerries landing. But the road winding through the fields ahead of her was empty in the heat haze and everything was roasted dry.Ivy coiled its way out of the brambles, and there were poppies out and blackberries too that were formed but not yet ripe. The sun shone through loops in the top half of the hedge, casting her a shadow-companion that stepped in time along the ditch; and the air coming in off the salt flats was thick and humid. She wiped the sweat from her face and her hand on her dress. There was no sign of anyone. The only sound was the scrunch of her sandals on the lane and the heavy puff of her breath.

She needed to decide what she was going to say. Her intention had been to think about it on the train but it was so noisy with all the servicemen heading this way that she’d hardly been able to think at all; and, besides, they had wanted to talk and joke with her, the only schoolgirl in the carriage. They bundled into her compartment, full of high spirits, sitting on each other and asking her questions that she’d rather not answer: what had she been doing all summer, what was her name, did she have any older sisters, any friends, were they pretty like her, and where was she going anyway, all on her own.

She wasn’t on her own, she had told them. Her mother was powdering her nose.

Oh, her ma’s powdering her nose! one of them said, mocking her perhaps, for he was red-faced and seemed a little drunk. He combed his fingers through his hair, stood up and saluted. Better make ourselves ship-shape then for the lady, lads.

But her mother never did come back; it was just something she had said in the hope that they’d leave her alone.

She tried to focus her thoughts, scanning the hedgerows for crickets and grasshoppers. Sometimes, if you clapped your hands loudly enough, five or six would leap up. Alfie and Eddie used to catch them in fishing nets, sweeping them through the air as the little creatures catapulted themselves out of the grass.

She stopped and put the suitcase down, readjusted her gas mask, and tried carrying the case with the other hand. Its cracked handle pinched at her fingers. She tipped her head back and looked at the vastness of the sky, so deep and blue. A top-notch day for flying, Alfie would say, but there were no planes, nor any birds. Even the sky was empty.

It had become something of a national obsession – sky-gazing. If she could see a plane, she told herself, everything was all right and it was just her being silly. She clambered up onto the verge to get a better look across the marsh, then looked up and down the lane, and listened, trying to hear a car somewhere, if not on this road, then another nearby, or a tractor in a field. Perhaps an army officer on a motorbike. Or the sound of a voice, the Local Defence Volunteers on drill somewhere, the sudden bark of an order. Or a dog. Even the bark of a dog would do. There had to be someone somewhere. The strange empty silence was making her uneasy. She could feel a tightening in her chest. She would not let herself cry.

She picked up the case again and carried on, walking faster now. A wind blew out from across the lagoons and reed beds, and stirred the grasses along the verge. Gorse seeds chased across the lane. And then a sudden sob erupted from inside her because she was so hot and tired now, and she hated this stillness; she thought she might choke on it. Where was everybody?

Maybe it had happened. She had heard people talking about it. She had heard the warnings on the BBC Home Service. She fumbled at her gas mask box, struggling to open it. That was why there wasn’t anyone about. That was why there weren’t any cars, any planes, birds, crickets, anything. She pulled the gas mask out, hurriedly slipping it over her head just as they had practised, and tugged the strap at the back, making sure it was secure. If they’d put something in the air… like everyone said they would… If they’d let something loose from a plane flying high above them… something invisible…

Inside the mask, her gasps for breath were louder than ever, the air hissing through the filter of the nozzle, the blood rushing to her head. The black rubber sucked against her skin, and the cellophane eyepiece started to mist up. She couldn’t see to either side because of the rubber rim blocking her vision. On an impulse she turned her head sharply, expecting to see someone, but the road behind her was still empty.

Breathe normally, Miss Mountford had instructed them during their drills. Breathe too hard and you’ll hyperventilate and then pass out or go mad. You might even give yourself a brain haemorrhage, they’d been told. You just need to breathe normally. But she never had been able to breathe normally in a mask. From the very first time she had put one on she had nightmares that one day she wouldn’t be able to take it off.

She tried to walk on, taking in gasps of air that never felt deep enough. Sweat and condensation began to collect inside the visor. It formed on her skin and ran down the sides, dripping around the rim of the eyepiece and into her eyes, making them water. Despite everything Miss Mountford had told them she was breathing so hard and fast now that she would almost certainly pass out. There were little tiny specks floating in the air around her. Tiny white specks. Just seeds, she told herself. Tiny seeds of something, she didn’t know what, touching the visor and her neck and her hands and prickling, tingling all over. She scratched at her skin; tiny pinpricks, perhaps every one an infection. She furiously flapped her arms about her, whirling them about and above her head, swiping at the air and its contagion until eventually she began to cry – and after all this time and all those promises to herself. Keep walking, she told herself. Keep walking. Don’t stop. Everything will be all right.

The road through the village was deserted. There was no one chatting, or cycling along the street. No children running along the pavements. No soldiers from the Liverpool Scottish leaning against the wall in their kilts and smoking; no Archie Chittock or Tommy Sparrow or any of the other Local Defence Volunteers messing about outside The Cricketers, their bikes piled beside them. Just dried leaves and dust blowing across the street.

As she reached the school, she saw the drawings that had been stuck to windows peeling away from the glass in the heat. Inside, the two classrooms were abandoned, the chairs upside down on the tables so that Mrs Sturgeon could clean the floor underneath. She pressed her hands against a window to look in and felt a sudden pang to see Rosie or Cath, or any one of the others, even Joe Pitcher, dashing in and sliding on his socks.

When she reached Pringle’s, the little village store was locked.In the doorway there was a small printed card that read in block capitals, WE ARE NOT INTERESTED IN THE POSSIBILITIES OF DEFEAT – THEY DO NOT EXIST. Despite this, the shop was closed and empty, gummed brown tape criss-crossing the windows in case a bomb-blast blew them in.

She walked across to the other side of the street, hearing the soft scrunch of her sandals, then undid the latch on Mr Morton’s gate and walked nervously up the stepping stone path, up to the front door. There were sandbags stashed against it that were green with mildew and sprouting grass, and on either side a gnome stood sentry with a rifle held against his red painted shoulder. Above her a tatty British flag hung limp from a pole. She pulled at the bell cord and stepped back as the two-tone chime announced her in the distant recesses of the house. She hitched up her socks as she waited and shined her sandals against the back of her legs as she always did, but all she could hear was her own voice, trapped in the mask with her, Please be in. Please be in.

She opened the letterbox, and, bending down, peered through. She could just about see down the hallway into the kitchen where Mr Morton always sat, his shirt stretching across his enormous back as he bent over his crosswords. He wasn’t there.

‘Mr Morton! Mr Morton? It’s me – it’s Lydia. Are you there?’

There was no reply. Not even from Mr Biggles, Mr Morton’s ill-tempered parakeet, who was known to throw abuse at every visitor that called.

She shut the letterbox and scrambled over the flowerbed to the sitting-room window. Like the windows at Pringle’s, it had sticky tape criss-crossing the glass and the curtains were drawn, a blackout cloth pulled across. She couldn’t see in. She stepped back and tried the letterbox again, pressing the nose of her mask against it.

‘Mr Morton! It’s me!’

She bent a little lower, staring through the murky visor down the empty hallway, then called again. She could hear the crack in her voice, the tears coming once more.

‘Please! Please! Are you there?’

But the house remained silent and eventually her hand slowly let the letterbox squeak back into place. She walked back down the path, shutting the gate behind her, and looked up and down the empty street. Everybody, it seemed, was gone.